The Andromeda Story

November 28, 2020

Hello everyone!

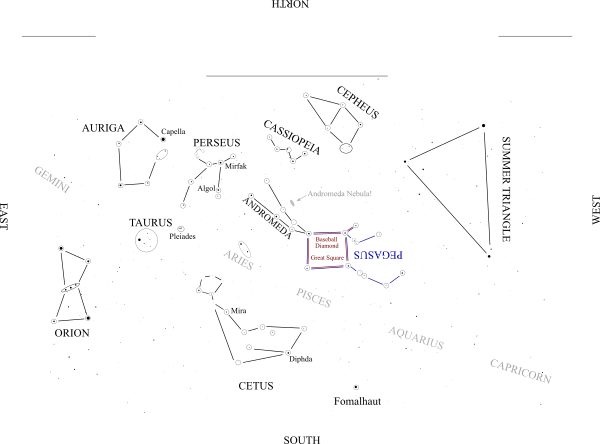

I hope you all are having a pleasant Thanksgiving break, and can afford some time to wander outdoors in the evenings and enjoy some stargazing. If so, I'd like to present a map of the evening skies in late November and early December.

I used to give students a blank worksheet with only stars on it, and we would then systematically identify stars one-by-one and circle them, and then connect the dots to make memorable shapes that we can give names to. This is how we would learn to recognize the landmarks in the sky, and I found that it made an educational and all-around popular classroom activity. I call this approach “geography class for the sky”, with maps of stars instead of normal maps. I suspect that it might be almost as fun and helpful for adults as it is for children. I've attached a blank version and a filled-in version of a handout representing the evening skies in late November and early December. You may simply used the filled-in version as a map. However, if you are teaching children, I suggest that the constellations will stick in their memories much better if you use the blank version as a practice exercise.

I've included most of the stars in the sky—the smallest may be hard to see on the paper, but they'll be hard to see in the sky, too, and depending on your sky conditions, you might not see them at all. I designed this worksheet for use in the classroom, which is why it has labeling blanks at the top for name, date, and title. Also remember, this map spans most of the sky, so expect the tiny constellations on the paper to be huge in the sky.

Shall we begin?

Orientation

This is a map of the overhead sky, which means you need to hold it over your head and compare it to the sky. But which way do you turn it? We need compass directions on the map to tell us. As you can see from the filled-in version, I've drawn this map with North and South at the top and bottom, and East and West at the left and right respectively. But...wait a minute...did I make a typo? Aren't East and West backwards? On most maps, if you read clockwise from north the directions proceed: North, East, South, West. (Or as my students would always cheer: “Never Eat Soggy Waffles!”) Can you see what's going on? Do you see an important difference between this map and normal maps?

As I said, this map is meant to be held upside-down, over your head. It's a map of the sky over you, while most normal maps are of the land under you. And when we flipped the map over, we reversed the directions. If you look at the star map from the wrong side, i.e. as if you were looking down on the sky from above, then the directions will be ordered the “right way”, in the same sequence as on a land map.

Now, what about the constellations? When I taught astronomy, we usually would have covered by now the constellations on the left and right, over the western and eastern horizons, and I'd rather not take the time to go into detail here. Most people are already familiar with Orion, anyway. The centerpiece of the evening sky, and of this map, is the cluster of constellations in the middle. So with apologies, I'm going to ignore Orion, Auriga, Taurus, and the Summer Triangle. I'll just make a quick comment about Capella, and the Pleiades. Capella is a helpful landmark, because it is one of the brightest stars in the sky, and the most northerly bright star, and it has three dim stars in a sharp isosceles triangle next to it, to help identify it. “Capella” is the diminutive of “capra”, the latin word for goat. This star is associated in mythology with a mother goat, and the dim stars nearby are associated with her offspring. It is not hard to recognize “Capella and the Kids”, and they are a very helpful landmark. In a month or so, I'll discuss Orion and Taurus, and maybe I'll say more about the Pleiades at that time, but I at least have to point them out here. The Pleiades cluster is a very close grouping of similar stars, and if you've never noticed them before, they are quite pretty. If you have a pair of binoculars, try aiming them at the Pleiades.

Now, for the main event...

The Andromeda Story

Perhaps one of the greatest stories from ancient Greek mythology is that of Queen Cassiopeia, her daughter Andromeda, and the hero Perseus. There have been many re-tellings throughout history. (I remember enjoying the 1981 movie Clash of the Titans as a child, but I haven't seen the more recent remake.) There are a few differences among the various tellings, but the gist of the story is as follows:

King Cepheus and Queen Cassiopeia ruled over the southern lands known at the time as Ethiopia. They raised a beautiful daughter and named her Andromeda, and Cassiopeia was so proud and boastful, she claimed that Andromeda was more beautiful even than the sea nymphs (the Nerieds). Comparing yourself (or your daughter) to deities was a big no-no, and Andromeda ended up chained to a rock, tormented and guarded by a huge sea monster. (Any kind of mysterious half-seen underwater leviathan, whether real whale or mythological monster, was known at the time as “Cetus”. The modern word cetacean, for the whale family, has the same root.) Fortunately, she was spotted by Perseus, on his way home from killing Medusa, possibly riding Pegasus. (This is one of the points where versions differ.) How could Perseus hope to defeat a giant sea monster? He remembered that he was carrying the head of Medusa, as proof of his deed. Without looking at it himself, he held up the head for the sea monster to see, and then, as happened to anyone who looked directly at Medusa, the sea monster was petrified—literally turned to stone. Perseus unchained Andromeda, they flew away into the sunset on Pegasus, and lived happily ever after. (If this story bears a certain resemblance to the medieval European tales of knights slaying dragons and rescuing princesses, that could very well be because the former story inspired the latter.)

The November sky contains all of the illustrations for this story. All of the major players in this drama have found their way into the immortal permanence of the stars, gathered together on their November stage. The king and queen, their daughter, and the hero that rescued her—they are all there. Pegasus is there, too, and even the sea monster Cetus. Even the head of Medusa is there.

Let's start with Cassiopeia, one of the more familiar shapes in the sky. If you can see all of the stars and have a vivid imagination, perhaps you can imagine a queen punished by being chained to her throne, and forced to spin in circles, hanging upside down for half of every day. But if we stick to simpler, brighter shapes, we can find an easy-to-recognize and easy-to-agree-upon “W” in the sky. Perhaps this can represent her crown. There's a bright and distinct “V” on the right half, and a flatter and dimmer “V” for the left half.

Her husband Cepheus is next to her, and is fairly dim. He is usually drawn as a square with a triangle on top. Perhaps the square could be his head, and the triangle a cap, like a sorcerer's cap? If you have trouble finding it, notice that the right side of Cassiopeia points at Cepheus' head. The brightest star in the area will be the bottom right corner of the box or “head”, and there's a cluster of small stars that will be the bottom left corner, and you can go from there. (If you can see all of Cepheus, dim stars included, and you want a way to draw it as a more complete and somewhat more realistic head, you can find such a drawing in “The Stars”, by H.A. Rey.)

In the overhead sky, near the “top” (or more formally the “zenith”), you should be able to find a near-perfect square of medium stars. It is not a very bright or very distinctive square, so if you want to be sure you've got the right stars, search the corners of the square for another medium star close by, making it look like a baseball diamond. This is another important, if less conspicuous, landmark in the sky. It is known as the “Great Square” or the “Great Square of Pegasus”.

Another way you can be sure you've found the right square is to look for a curved chain of 3 or 4 stars coming off of the other corner, and gracefully arcing around Cassiopeia. The first three form the most distinctive part of Andromeda, and the final star technically belongs to Perseus. However, before you draw in any constellations, just imagine (or maybe lightly pencil in) the square and this entire chain of stars coming off of the corner. I would do this on the board, and my students would always say: “It's another Dipper!”. If you look very closely at the Pleiades, you might think that it looks like a tiny dipper as well. So in the sky overhead, not too far from Cassipeia, we have the “Super Duper Dipper” and the “Itty Bitty Dipper”. (I find it helpful to remember the “Super Duper Dipper”, but it is definitely not an official constellation. It is only something I made up with my students.)

Let's return to our story, and draw in the daughter of Cassiopeia and Cepheus, and the namesake of this story: Andromeda. Coming off of the same corner of the square and running more or less parallel with the first arc is a second arc of three more dimmer stars. We can think of the corner of the square as her head, the center sections of the two arcs as her body, and the final sections of the arcs as her legs. If you look very closely, you might even find a trail of faint stars cutting across sideways that you could use as her outstretched arms.

I fear this newsletter may already be too long, but I have to at least point out a spectacular nebula, one of the few you can see without a telescope. Find the second star in the brighter chain of Andromeda, hop over to the second star in the dimmer chain, then hop about the same distance again, and you should come to a dim fuzzy patch in the sky. A hundred years ago, scientists thought that this was a cloud or “nebula” like any other. Then Edwin Hubble, with the most powerful telescope in the world (at the time), revealed it was made up of uncountable individual stars, far more than any known star cluster. Not only that, but by measuring the fluctuations in some of these stars, scientists soon figured out a way to measure how far away these stars are—2 million light years! As ridiculously fast as light is, it still takes 2 million years for the light to travel from there to here! That's thousands of times farther than any known “normal” star. This was the first time that astronomers realized that the Andromeda nebula was its own armada or “galaxy” of stars, separate from our own. This was the discovery of galaxies. The Andromeda Galaxy is the only galaxy you can see with your naked eyes (if you don't count the Milky Way), and it can be a beautiful sight in a pair of binoculars.

If you follow the bright left side of Andromeda and keep going, this takes you to Perseus. Some constellations, like Orion and the Big Dipper, have distinct shapes that evoke an image of a common thing, and many people see the same thing. Perseus is not one of these. He is a fairly bright constellation, but without a familiar shape, and he can be drawn in a number of ways. If you have very lousy skies and can only see the brightest stars, it may work best to think of him as a capital “T”, formed by connecting the two brightest stars in a vertical line, then using the two nearest medium stars to form the cross-bar. I think of him as a Greek π (pi). I'm sure you have seen a movie or TV scene where Clark Kent is running off to save somebody or other, and he pulls open his shirt to reveal the “S” for Superman? Well, I think of Perseus doing the same thing, except his chest reveals a "π", for Perseus. It's silly, but it helps me remember Perseus in the sky. (If you want to see H.A. Rey's attempt to make Perseus look like an actual person, I again recommend his book “The Stars”.)

Let's return to the Great Square, and draw in Pegasus. This is one constellation where I disagree with H.A. Rey. His goal was to make simple stick-figure drawings for all of the modern “official” constellations, and make them look like what they are named after. The upper left corner of the Great Square is technically not part of Pegasus in modern astronomy books, so he excluded it, and he tried to make a complete winged horse from the rest of them. He did an admirable job given the limitations, but my eye just can't accept his drawing as attractive or memorable, especially when, if you turn the drawing upside-down, it looks so much like the front end of a galloping horse. Try it! Furthermore, this must be the way our ancestors saw it, at least in medieval times, because the Arabic names for the stars translate into the corresponding parts of a horse. The name for the “head of Andromeda” actually translates to “navel”, and the name for the outermost star that I have drawn as the end of the horse's head translates to “nose”.

So: Turn the drawing upside down, find the “umpire's plate” of the “baseball diamond”, and that becomes the lowered foreleg of the galloping horse. Find three dim stars above that one, and turn those into the other foreleg. Jump from the upper left corner (of the turned-over square) to two stars nearby, then up again, then down and left to the brightest star in the area, and you have drawn in the horse's neck and head.

Finally we come to Cetus, the sea monster that imprisoned and tormented Andromeda. I have no idea how the ancients saw the shape in these stars, and I like H.A. Rey's cute drawing of a whale, so I borrow this shape completely from him. The brightest star in the area is Diphda, and that serves as the corner of his mouth. If you are a teacher, I'll let you work out the best way to describe how to connect the dots to make the rest of the whale's head. I found the tail to be somewhat hopeless. A few students were great at copying me. (I used a digital projector to shine the worksheet onto a whiteboard, and then I drew in the constellations with a marker.) But half of the students just free-handed the tail. That may be just as well, since so many of the stars in the tail are really dim. Sometimes you just have to fudge it. For myself, I find the same thing applies in the sky. I can usually identify the head of H.A. Rey's whale in the stars, but I often have difficulty tracing out the tail. (It may also work just to let students make up their own shapes, if that helps them identify and remember the constellation.)

Bizarre Stars

The Andromeda Story in the sky is home to three rather odd stars, all of which serve as prototypes in the modern star classification system.

The Arabic name “Algol” is related to the English word “ghoul”, and can be translated as “demon”. In classical times, this star was seen as the head of medusa, being held at arm's length by Perseus. Algol is the demon star. It probably got its name because...it winks. Normally it is a bright star, almost as bright as nearby Mirfak. Every 3 days (2.87 to be precise), it dims. It doesn't turn all the way off, or even get super-dim, but it gets dim enough that it stops being the second-brightest star in Perseus, and joins the ranks of the other hum-drum stars in the area. It stays dim for a couple of hours, and then it returns to normal. On some nights, if you stay up long enough, you can see the demon star wink at you.

If you wish to watch this phenomena for yourself, Sky & Telescope has a helpful web page on the “Minima of Algol”. According to that web page, the next four minima of Algol will occur at...

| Universal Time | Central Time | Pacific Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11/30, 10:05 UT | 11/30, 04:05 am | 11/30, 02:05 am | ||

| 12/03, 06:54 UT | 12/03, 00:54 am | 12/02, 10:54 pm | ||

| 12/06, 03:43 UT | 12/05, 09:43 pm | 12/05, 07:43 pm | ||

| 12/09, 00:32 UT | 12/08, 06:32 pm | 12/08, 04:32 pm |

You may also notice the star named “Mira” in Cetus. Or rather you might not notice it. Sometimes it isn't there. That's the reason for the name: This is the “wonder star” or the “miracle star”. Mira changes brightness like Algol, but Mira changes so much, sometimes it becomes invisible. Roughly every year, it goes through a cycle, rising in brightness for roughly 100 days, and declining for roughly 200 days. The last maxima was two months ago, so maybe you can still see it, but not for long. The next maxima is predicted for August, 2021.

Both Algol in Perseus and Mira in Cetus were probably known to change by the ancients, but it is hard to tell, due to a lack of definitive evidence. There is a third changing star in Cepheus that was discovered to vary in 1784 by a teenager.

In 1782, John Goodricke, deaf and aged 18, was given the opportunity to work in an observatory in York, England, and he carried out a series of careful observations of Algol. He then became the first person in history to offer a reason for why the star went through these sudden drastic drops in brightness. Can you think of one? What might cause a star to suddenly appear dimmer, for a brief time, at regular intervals? Goodwicke suggested that something dim, maybe a dimmer star, was orbiting the main star, and passing in front of it with every orbit, thus blocking some of the light. If one star orbits another, it might cause eclipses. Astronomers now view Algol as the protoype star for the family of eclipsing binaries.

Shortly thereafter, Goodricke turned his attention to other stars, and for the first time, discovered that “delta Cephei”, one of the stars in Cepheus' “mouth”, also varies, from dim to quite dim, every 5⅓ days. This is now the prototype star for another family: Cepheid variables. The interesting thing about Cepheid variables is that they pulse in a very regular way, at a rate that is directly related to their brightness. The faster they pulse, the brighter they are. Thus, being able to measure the rate of pulsation, which tells how bright a star should be, and being able to measure how bright a star appears to be in the sky, astronomers can now measure how far away stars are, even to distances as far as other galaxies. Remember the discovery of the Andromeda Galaxy? It was Goodricke's discovery of Cepheid variables that made it possible.

Goodricke was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1786, and died four days later from pneumonia, at the age of 21. A promising life tragically cut short by illness.

Stars do not always have the same, steady brightness. Many of them don't. Depending on how closely you measure, most of them don't. We call stars that change their brightness “variables” or “variable stars”. Algol is the prototype for eclipsing binaries, Mira is the prototype for “Mira variables”, and delta Cephei is the prototype for “Cepheid variables”, which help astronomers to measure the universe. And all three of these stars are found in the constellations of the Andromeda Story.

The Zodiac

Just a quick final comment about the zodiac: If you haven't noticed yet, the zodiac runs right across our scene. As you may know, the significance of the zodiac is not in the constellations themselves. Many of them are quite dim and unremarkable. Capricorn and Aquarius have no bright stars, and Pisces doesn't even have any medium stars. Capricorn and Aquarius can be a challenge to identify in the city, and Pisces can be a challenge even in dark skies. Instead, the zodiacal constellations are special because those are the ones containing the planets.

The “wandering stars” don't wander just anywhere. They can't trespass in just any old constellation. They are confined to a “highway” through the stars, and we remember that highway by noting the special set of constellations that mark the path. The moon and sun are confined to the same highway as well. Many of these marker constellations represent animals, and this “planet highway” came to be known as the zoo-diac. (The root word of zodiac, zoo, and zoology, is zoon, the Greek word for animal.) In modern terms, we can call the zodiac the “solar system in the sky”, and you can see the solar system if you can recognize the zodiac.

If you are out in the evenings for the next week or several, you can find Jupiter and Saturn above the western horizon, near the boundary between Sagittarius and Capricorn. Mars is higher in the sky, and is currently in one of the zodiac constellations closer to the middle of the page. Can you tell which one? Can you tell which zodiac constellation the moon is in?

(By the way, I just wandered outside to double-check some of my claims in my own sky before I sent this letter, and I was reminded that we currently have a nearly full moon. That doesn't help stargazing at all. To see some of the dimmer and more interesting things that I mentioned, you may need to wait a week or two. The Andromeda Story will continue to be visible overhead in the evenings for a month at least, it will just shift a tiny bit more westward every day.)

Happy Viewing!

John

P.S. Did I get carried away? This seems like a long newsletter.