Counting the Stars in Pegasus

November 4, 2021

Well, farewell to my favorite month of the year. Here in Iowa, some dried-out maples are still clinging to the last remains of their beautiful colors, but the woods now are mostly filled with the cold skeletons of hibernating trees. We have also had our first hard freezes of the year and now the bugs, bats, and mice are all trying to come indoors. I suppose it's time to say goodbye to the joys of fall and start looking forward to the holiday season instead.

The start of the 2021 Holiday Season will also coincide with the second Eclipse Season of the year, comprising a lunar eclipse on November 19 and a solar eclipse on December 4. You will not be able to see the solar eclipse unless you are a penguin, or if you board an eclipse-following cruise ship bound for the Antarctic Ocean. That eclipse will only be visible near the South Pole. The lunar eclipse later this month will be visible in North America, and portions of it will be visible in South America and the Pacific Rim, but I want to discuss that separately. So I'll send another newsletter in about a week covering the lunar eclipse. Today I just want to make a quick announcement and to discuss some casual November stargazing that you can do prior to the eclipse.

My First Book!

First, the announcement: I just published my first book, The Discovery of Germs, about the scientific discovery of parasitic microbes as the cause of contagious diseases. This newsletter is supposed to be about astronomy, but if you're interested in astronomy education, perhaps you'll also be interested in science education or the history of science more generally.

The Discovery of Germs is about 100 pages long, it's aimed at young adults (roughly high school age), and it covers the period from the invention of the microscope in about 1600, to the triumph of the "Germ Theory of Disease" in the late 1800s. I hope I succeeded in telling a fascinating and inspiring story, but I was also hoping that the book could be useful to parents or teachers by serving as a sort of textbook, and by providing the basis for several lessons or discussions on the microscope, microbes, and the scientific method. (I'm thinking of writing a "teacher's guide" to go along with the book, but that's not going to happen soon.)The book is available in paperback and electronic form from most major booksellers. (Here's the Amazon link). But I'll be happy to send any reader of this newsletter a free digital copy (EPUB or PDF), in exchange for a review on Amazon after you've read it. Just reply to this email and say “I want a copy!”

Evening Stargazing

If you have been reading this newsletter for a while, you may recall the “solar system in the sky”. For the last month or two the two brightest planets (Jupiter and Venus) and the slowest visible planet (Saturn) have all been up in the evening skies. By connecting the dots in your imagination, you can visualize the “planet highway” across the sky, especially if you can also find the sun and the moon on the highway. In other words, this array of movable objects allows you to easily see for yourself the zodiac, or the “solar system in the sky”.

This month, Jupiter and Saturn will continue to approach Venus, meaning that it will be harder to trace the complete semicircle from horizon to horizon, but the concentration of “wanderers” all in one place will make the “solar system” at this place in the sky all the more breathtaking.

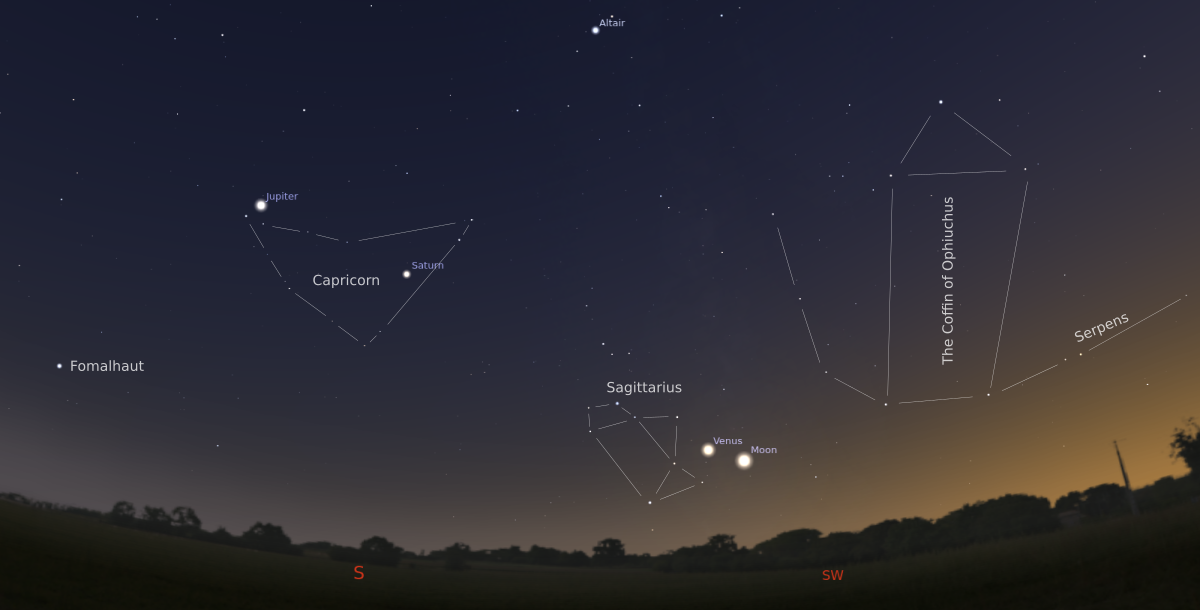

The following picture shows the view from northern mid-latitudes, facing south, about an hour after sunset, on Sunday the 7th. (To be more precise, it shows the view from Iowa. If you live farther south, all of the interesting stuff will be even higher and more beautiful. If you live in Canada or Europe, unfortunately, it will be lower, and possibly hidden by the horizon. If you live in the Southern Hemisphere, you will need to imagine the scene upside-down in the northern sky instead of the southern sky.) Except for the moon, the scene will be pretty much the same for the next week or two.

(By the way, I'm aware that the details in my pictures are rather small. You can try viewing the image full-screen by right-clicking on the image. If that doesn't work, you can always go to the archive version on my website, and right-click on the image there.)

If you go outdoors and face south after sunset, the first thing you will notice will probably be Jupiter, and to the right of Jupiter you should find Saturn without too much trouble. Both Jupiter and Saturn are currently in Capricorn, but that's a pretty dim constellation, and hard to find in most skies. If you have very clear, dark skies, see if you can trace out the cornucopia shape. (Or perhaps the grin of the Cheshire cat?)

Low in the southwest will be Venus. If you have a clear horizon, you should have no trouble seeing it, but it will be quite low, especially if you live farther north than I do. If you can see it, see if you can trace out the teapot shape of Sagittarius next to it. (Venus actually just passed “greatest elongation” on October 29, meaning it was as far from the sun as it could go. It will now turn around and start to sink back into the sunset as the weeks go by. Unfortunately, at this time of year, the “highway” or “zodiac” is highly tilted, so even though Venus is far from the sun in the sky, it is still troublingly close to the horizon.)

If you can still see the glow of sunset, use your imagination to find the sun below the horizon. Now if you connect the dots from the Sun to Venus to Saturn to Jupiter, you will have traced out the “planet highway”, or the solar system in the sky.

Today the 4th is the date of the November New Moon, meaning that the moon is currently next to the sun. Over the next week, it will appear higher over the sunset every night, and will gradually proceed eastward night-by-night. Watch for it to march along the “planet highway” over the coming week, passing first Venus, then Saturn, then Jupiter, and growing from a thin crescent to a quarter moon as it goes. The sunsets on Sunday and Monday should be especially lovely, with Venus and a thin crescent moon decorating the sky over the glowing horizon.

Overhead, look for the south-pointing Summer Triangle, with Altair and Altair's medium companion star marking the tip of the triangle. Above the sunset will be Serpens (the long graceful U-shaped curve of stars) and Ophiuchus the serpent-holder (most easily recognized by the characteristic “coffin” shape). Ophiuchus is traditionally seen as a man wrestling with a snake, but modern cartographers of the sky don't like overlapping constellations, so they decided to split the pair of them into three pieces. If you consult a modern star chart, you will find Ophiuchus in the middle, with Serpens Caput (Serpent's Head), and Serpens Cauda (Serpent's Tail) on each side. To the left of the scene, or the east, you may find Fomalhaut. Fomalhaut is usually easy to see, but hard to recognize, because the rest of its constellation (Piscis Austrinus) is extremely dim.

The Leonids

We also have a famous meteor shower in November, but if you are like me, and you are only willing to go to the trouble of spending an hour outdoors in the middle of the night if there's a good chance of an impressive spectacle, then you probably shouldn't concern yourself with this one.

The November Leonids are known for their spectacular storms ... every 33 years. And we are still a decade from the next expected storm. In off-storm years, you can expect rates under ideal conditions of maybe 10-15 meteors per hour. But that's only under ideal conditions. This year, even if you can find a dark place to watch the sky for an hour or two in the wee morning hours, the peak of the Leonid shower (on the 16th) is going to occur three days before the full moon (on the 19th), and the nearly-full moon will probably drown out many of the meteors.

Incidentally, if you want to get a feel for how clear your skies are, go outdoors in the evening, and after enjoying the view over the sunset, turn and face east.

This is the view from the same place and at the same time as the last picture, but facing east instead of south. (If you live to the north or south of Iowa, you will have to use your imagination to rotate the picture clockwise or counter-clockwise, respectively. If you live in the Southern Hemisphere, Jupiter will be high in the sky, and Cassiopeia will be hidden below the northern horizon.) In front of you, you may be able to find a large square of medium stars. There is another star above the top corner, making it look like a baseball diamond. There is also a graceful curve of stars coming off of the left corner, looking something like a handle. (If you ignore the “umpire” of the baseball diamond, you might think it looks like another dipper. My students and I would call this the “Super-Duper Dipper”.)

Officially, the square belongs to the constellation Pegasus, and the graceful curve belongs to the constellation Andromeda. After finding the square, try to see how many dim stars you can find inside the square. This can be a helpful indicator of how clear and dark your skies are. The more stars you can see in Pegasus, the more meteors you will be able to see. If you can't see any, or if you can't even find the square itself, then you have lousy skies (or lousy eyesight). Abandon all hope of seeing meteors. Ten stars is pretty good. Thirty is spectacular. In a nutshell, if you can see more than a few stars inside the Great Square of Pegasus, then you have pretty good skies, and you may want to try meteor-watching later that night. (You may also want to try looking for a dim fuzzy patch above the middle star of Andromeda. That used to be called the Andromeda Nebula, until it was discovered to be thousands of times farther away than even the most distant stars...)

If you really want to watch for Leonids, then this coming week, when the moon will be absent from the morning skies, might be better. The peak of the shower will be on the 16th, but the shower is already ongoing, so if you have good skies, and you patiently brave the early morning cold, you might be able to catch a few beautiful meteors.